A small number of sick children left the hospital against medical advice and had 2 times the risk of death post-discharge compared to children who did not leave against medical advice. |

|

KEY MESSAGE Follow-up for recently hospitalized children can be strengthened. Consider:

|

Background | Findings from the Chain Study | What the Chain results mean | Chain Information

Background

Children admitted to hospital are at higher risk of mortality in the year following admission, compared to non-hospitalised children in the same communities. A study in Kenya suggests there is a nine-fold increased risk of mortality in the subsequent year after hospital admission.1 Death following discharge from hospital (post-discharge mortality) occurs in 5-8% of children who leave hospital after a general paediatric admission in low- and middle-income settings. Often, children may be as likely to die after discharge as during the inpatient period.2

One group at particularly high risk are children who leave against medical advice; these children have been shown to be as much as eight times more likely to die than those who complete their inpatient treatment. The most prominent reasons for leaving against medical advice include disagreements with nurses and doctors, mistrust of the health system or treatments, financial concerns such as bills or lost income, and lack of social support.3 However, much of the data that inform these risk factors comes from higher-income settings. There are limited studies on factors contributing to leaving against medical advice in low- and middle-income settings.

Findings from the CHAIN cohort

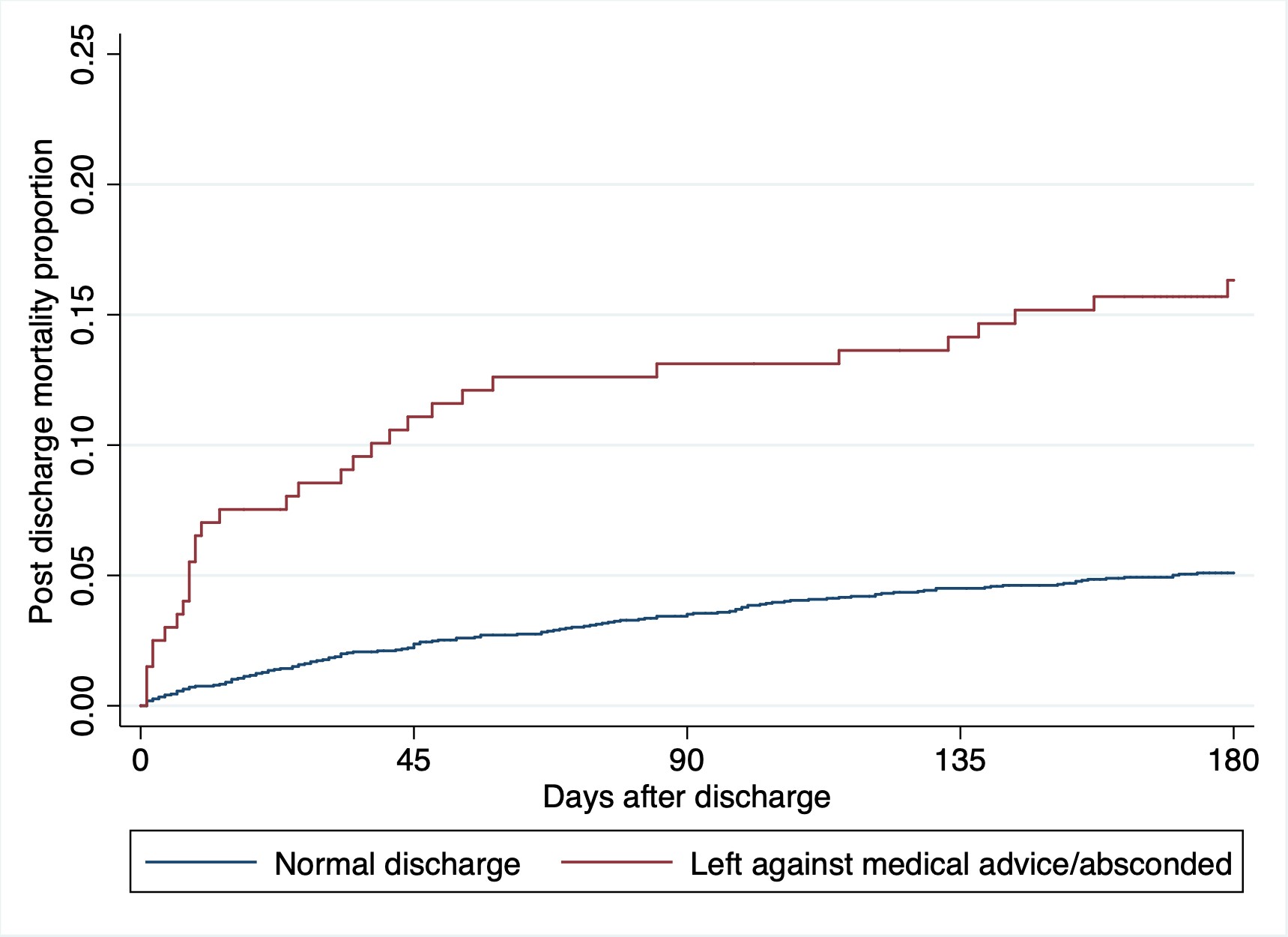

CHAIN enrolled 3,101 children at nine hospitals in six countries across Africa and South Asia. Among all children who survived to leave hospital, one out of every 15 patients did so against medical advice. Children who absconded or left against medical advice were 2.5 times more likely to die in the six months post-discharge than were children who were discharged in the usual way (HR: 2.53, 95%CI: 1.61-3.99). Reasons for leaving against medical advice included factors such as maternal mental and physical health, education, employment, household resources, and food insecurity.

Interviews with families within CHAIN provided further insights into leaving against medical advice.4 Social and economic concerns can often lead families to try to minimize the duration and costs of inpatient stays. Many families draw on savings or borrow money to cover hospitalisation costs. Even if hospital care itself is free, there are hidden costs, including travel, accommodation, and bed charges and food for parents and caregivers. These expenditures, as well as loss of income, have knock-on effects for other children and caregivers in the household, including family members who reported missing meals and/or school to pay for the hospitalisation. While hospital staff were usually supportive of families and their needs, some mothers reported stigmatization and accusations by staff that families were trying to use hospitalisation to gain access to food or other resources.

What the CHAIN results mean

Strategies that reduce leaving against medical advice are urgently needed. Early identification of families at risk of leaving and helping address concerns and reduce direct or indirect costs of admission may be beneficial. This involves building a strong therapeutic alliance between ward staff and the child’s caregivers. This would need to be adapted to local contexts in order to be optimally successful.

For families that do still leave against medical advice, clinicians should implement a discharge care plan that recognizes the increased risk of death faced by these children and attempt to mitigate such risk through the use of take-home medications, patient education, and down-referral to community health workers and clinics close to the family’s home. The number of patients leaving against medical advice should also be monitored as a performance indicator in hospital and departmental audit activities.

Figure 1. Post-discharge mortality rates for children leaving against medical advice

-

Moisi JC, Gatakaa H, Berkley JA, et al. Excess child mortality after discharge from hospital in Kilifi, Kenya: a retrospective cohort analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2011;89(10):725-32, 32A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.089235

-

Nemetchek B, English L, Kissoon N, et al. Paediatric postdischarge mortality in developing countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018;8(12):e023445. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen2018-023445

-

Albayati A, Douedi S, Alshami A, et al. Why Do Patients Leave against Medical Advice? Reasons, Consequences, Prevention, and Interventions. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(2):111. Published 2021 Jan 21. doi:10.3390/healthcare9020111

-

Zakayo SM, Njeru RW, Sanga G, et al. Vulnerability and agency across treatment-seeking journeys for acutely ill children: how family members navigate complex healthcare before, during and after hospitalisation in a rural Kenyan setting. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):136. Published 2020 Aug 10. doi:10.1186/s12939-020-01252-x

Acute Care | Discharge | Leaving Against Medical Advice | Stigma and Wasting

Partner Organisations: