Sick children who are very thin (malnourished) are 5 times more likely to die in hospital or after discharge compared to non-thin children. |

|

KEY MESSAGE Take children who are thin or not growing well to medical care before they develop any sickness like pneumonia and diarrhea. |

Background | Findings from the CHAIN Study | What the CHAIN results mean | CHAIN Information

Background

The Childhood Acute Illness & Nutrition (CHAIN) Network brings together health care providers, scientists and communities to generate evidence in order to help undernourished children survive, thrive and grow during and after an acute illness in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). When children become sick, mortality rates in LMICs are far higher than in higher-resource settings, despite following available management guidelines. Children in these settings also have a markedly increased risk of death at home following discharge from hospital. Ultimately, CHAIN aims to identify modifiable pathways leading to mortality in order to improve survival among high-risk children in LMIC settings.

The first step in addressing the high mortality observed in LMIC settings is to understand which children are at highest risk. Several clinical risk scores have been previously devised, usually based on clinical features and measuring nutritional status at admission. However, few of these scores are validated and none are used at scale or have had major impact. Importantly, most scores do not include an assessment of risk of death following discharge or include important social risk factors. While we know that nutritional status is a strong predictor of death despite treatment, it does not identify specific deficiencies or causes of mortality that need to be addressed.

The first step in addressing the high mortality observed in LMIC settings is to understand which children are at highest risk. Several clinical risk scores have been previously devised, usually based on clinical features and measuring nutritional status at admission. However, few of these scores are validated and none are used at scale or have had major impact. Importantly, most scores do not include an assessment of risk of death following discharge or include important social risk factors. While we know that nutritional status is a strong predictor of death despite treatment, it does not identify specific deficiencies or causes of mortality that need to be addressed.

The CHAIN cohort enrolled children from 2 to 23 months old who were hospitalised with an acute illness at nine hospitals in six countries. Enrolled children were grouped by nutritional status (NW = not wasted, MW = moderately wasted and SWK = severely wasted or kwashiorkor). They were followed up in hospital and for 6 months after discharge from hospital.

Findings from the CHAIN cohort

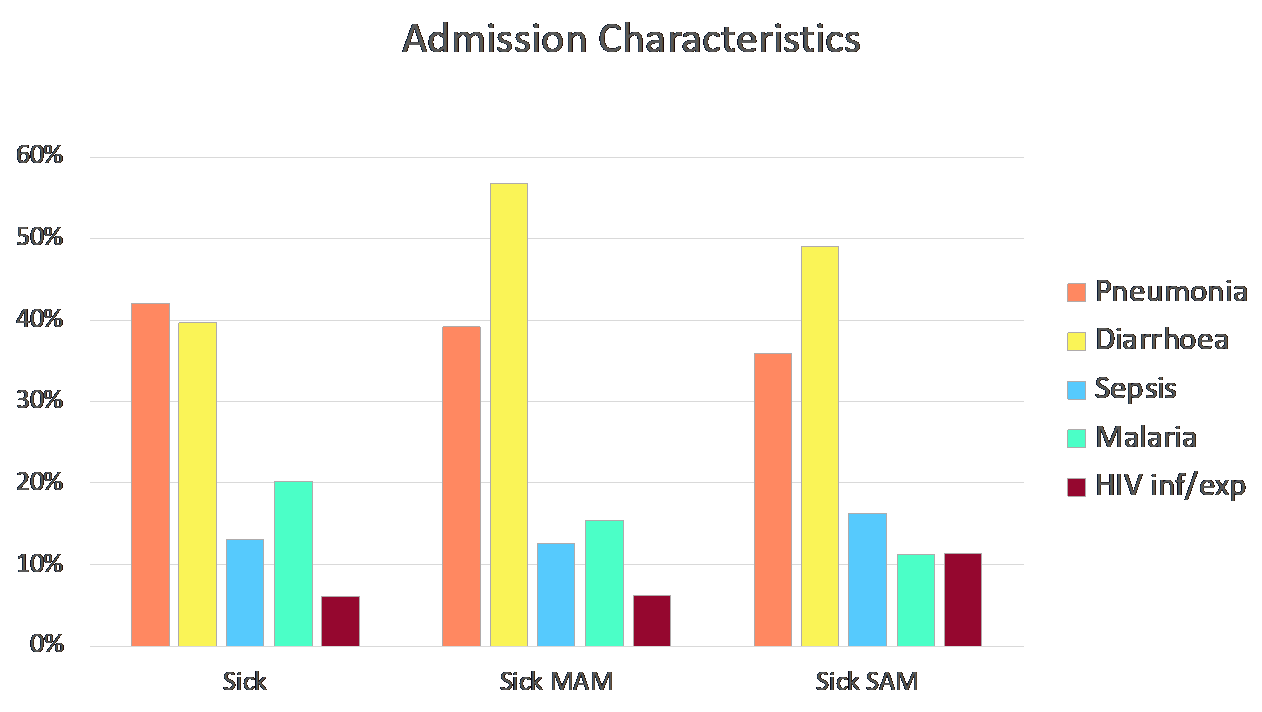

Of 3,101 children enrolled, diarrhoea, pneumonia, sepsis and malaria were the most common conditions across all three nutritional groups.

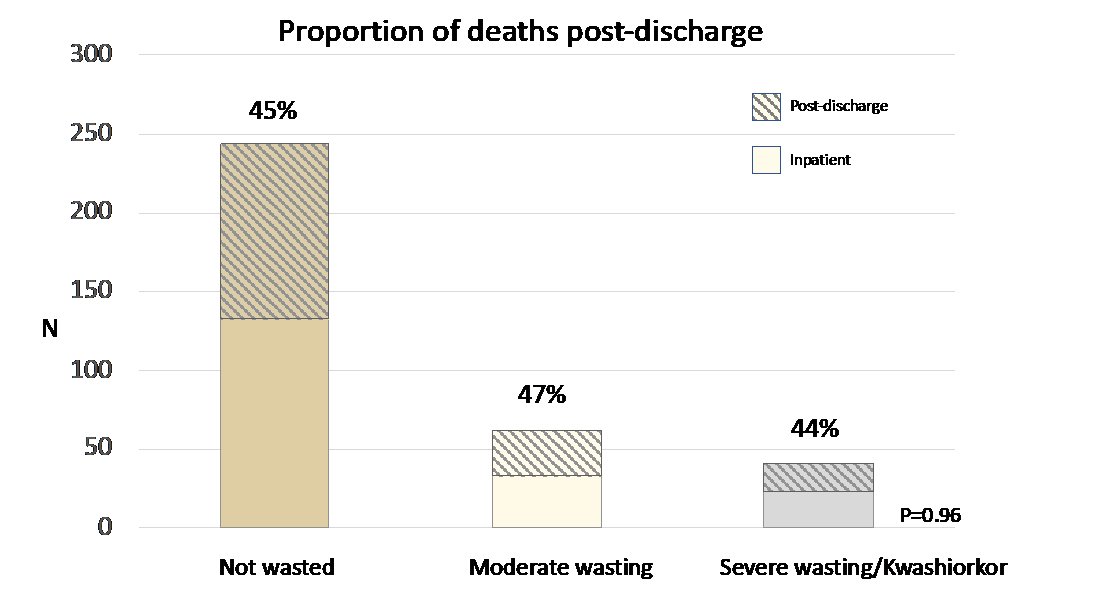

Overall, 350 (11%) children died. Mortality was strongly associated with nutritional status. Across all three nutritional groups and sites we saw that about half of all deaths (52%) occurred in hospital and half (48%) happened after discharge. The rate of post-discharge death was highest in the first 2 weeks after discharge. These findings suggest that many deaths may be due to incomplete treatment of acute illness or failure to identify and treat all underlying conditions.

CHAIN found that simple clinical signs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Conscious level) plus information about the child’s mother (Do they work? Have independent income? Are there mental health issues?) and comorbidities (HIV, stunting, sickle cell disease, haemoglobinopathy, heart disease) predicted mortality during the first 30 days from admission. Both inpatient and post discharge deaths were equally predictable.

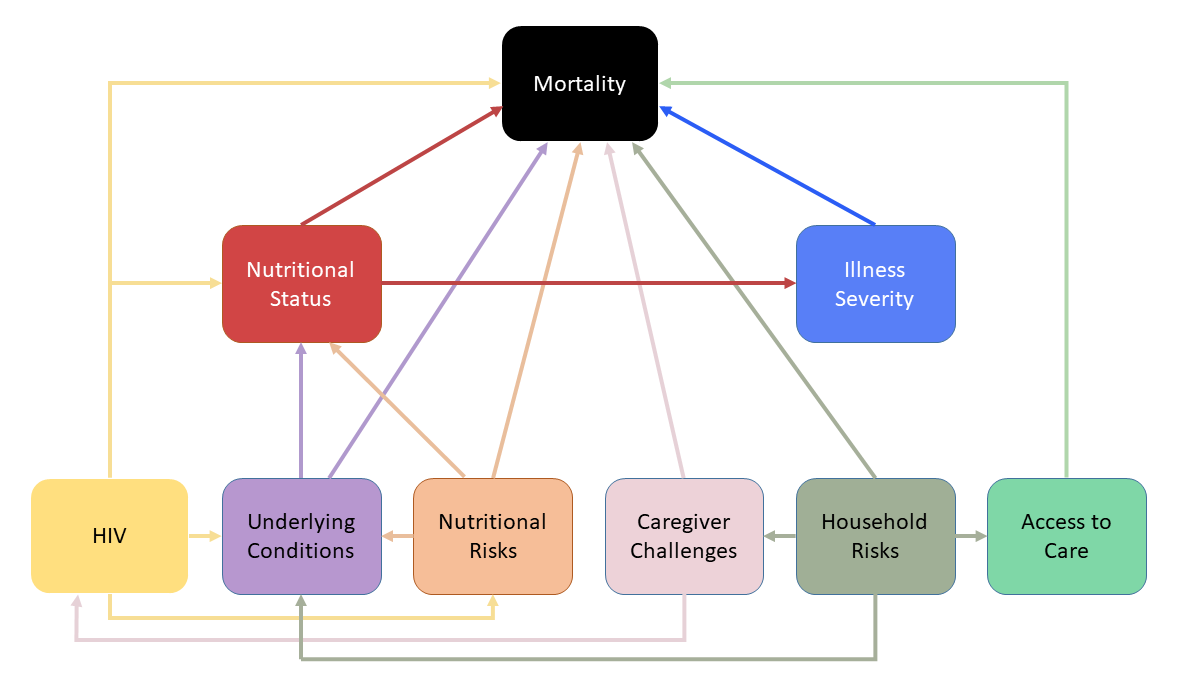

Many of the underlying pathways leading to mortality operated through nutritional status, suggesting that this is not only measuring the impact of nutritional intake, but is also detecting the impact of social factors and maternal issues not corrected by medical treatment or feeding programmes.

What the CHAIN results mean

Importantly, as well as high-risk children, a large group of very low risk children were also identifiable. Early review and discharging such low-risk children earlier may reduce pressure on resources and staffing. The identification and management of these children should be guided by formal criteria established at a hospital-level or by national paediatrics bodies, especially as these decisions are often made may less experienced clinical staff. This would allow nurses and clinicians to focus on children at higher risk of death.

At discharge, nearly half the deaths have not yet occurred. WHO and national guidelines contain few recommendations for who to follow up and how often. In some situations, formal down-referralto the responsibility of a named clinic or community health worker could be implemented. Deaths after discharge often occurred rapidly after families noticed that the child was deteriorating. This means that training mothers and families on danger signs may be helpful in accelerating access to care and treatment. Further, regular follow up can be done by phone (daily if necessary) to check on a child’s progress and any signs of deterioration. Post-discharge follow-up can also be structured to prioritise those at highest risk of mortality, including children who leave against medical advice, are malnourished, still have some clinical signs at discharge or have challenging social circumstances.

Acute Care | Discharge | Leaving Against Medical Advice | Stigma and Wasting

Partner Organisations: